Hainan Treasures in Su Dongpo's Poems

In 1097 AD, Su Shi (Su Dongpo), a polymath and man of the people who lived during the Northern Song Dynasty, was removed from his official post and banished to Danzhou on the west coast of Hainan. The Hainan of a millennium ago was synonymous with remoteness and wildness in the minds of people in China's Central Plains. To them, being banished here was a fate worse than death. For Su Dongpo, however, the initial despair of being sent down to a remote corner of the empire gave way to a sense of belonging. Gradually, Hainan's beautiful scenery, unique products, and simple folk customs took root in the old man's heart. After being itinerant for most of his adult life, he eventually felt at home in Hainan and was reluctant to leave: "In truth, I am from Danzhou. Sichuan is merely where I was born."

During his three years of exile in Hainan, Su Dongpo observed his environment with a keen and humanistic heart, integrating into local life and crafting a large number of poems. With many of them surviving into the present day, these poems have allowed people in later generations to appreciate the literary spirit and character of Su Dongpo, who was already a celebrated great writer in his lifetime, as well as the unique facets of this tropical island.

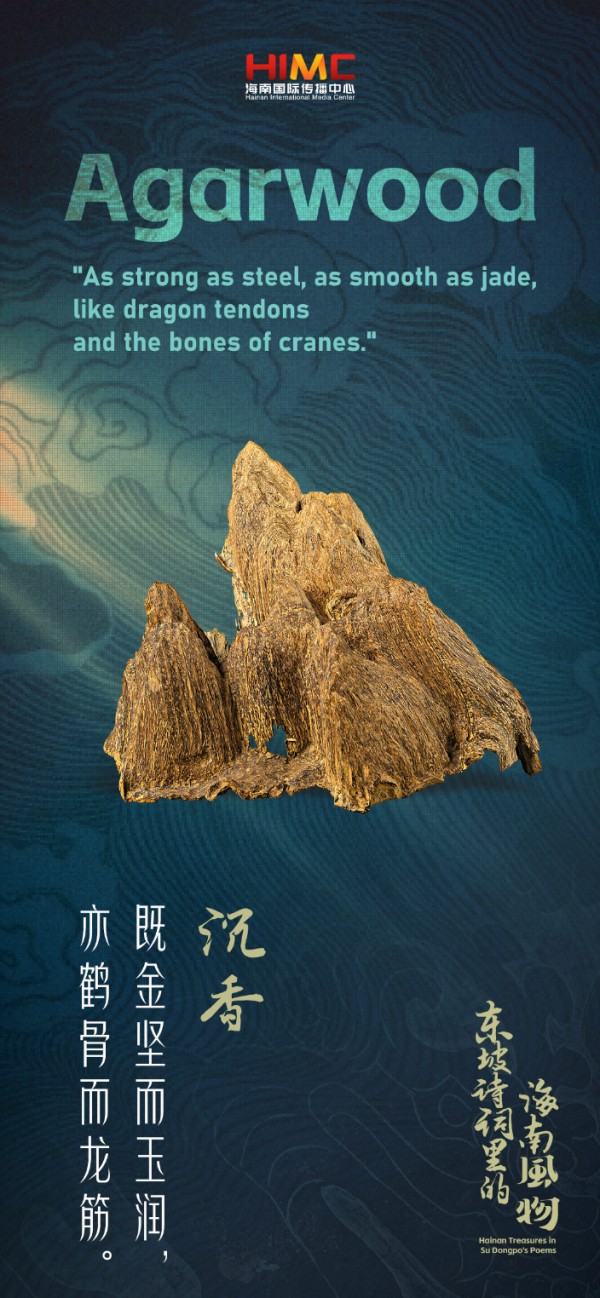

Backstory:

While Su Dongpo was living in exile in Danzhou, his younger brother, Su Zhe, turned 60, a particularly important anniversary in Chinese culture. The older Su sought out a piece of agarwood in the shape of a mountain ridge as a birthday gift for his brother, composing the accompanying prose poem, "On the Qualities of Agarwood." By ascribing noble, gentlemanly virtues to agarwood in the poem, such as remaining steadfast and detached from one's ego, Su Dongpo hoped to inspire and comfort his younger brother, who was also facing severe adversity.

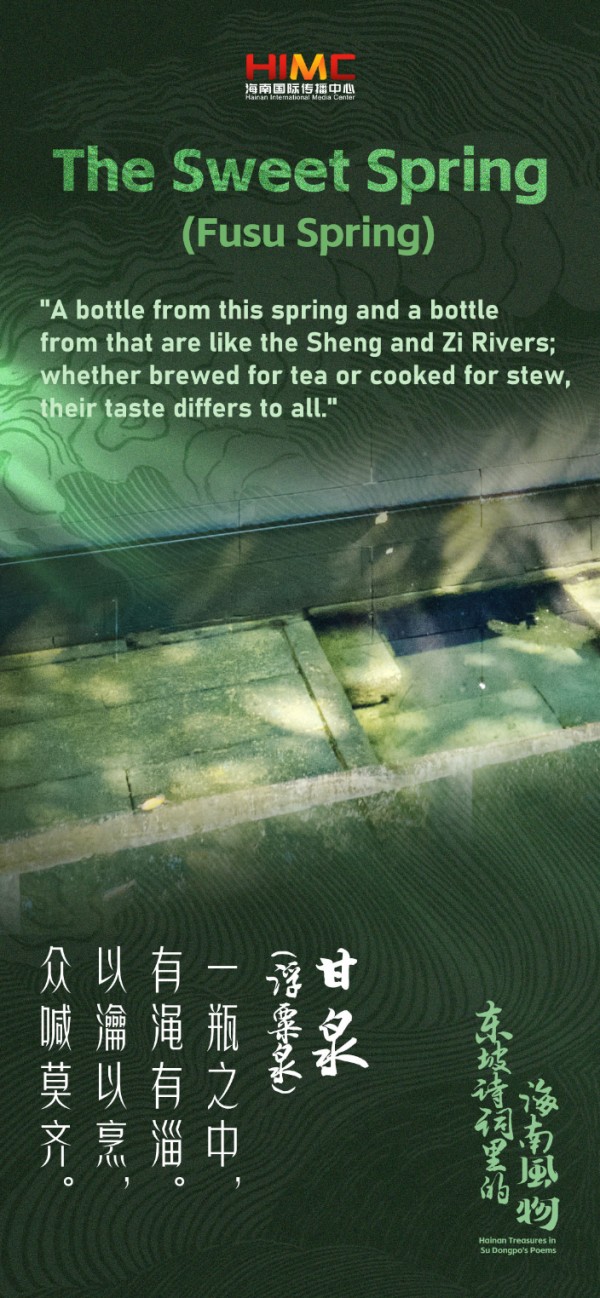

Backstory:

While on his way to exile in Danzhou, Su Dongpo passed through Qiongzhou Prefecture (present-day Fucheng area in Haikou), where he saw locals scooping water straight out of a nearby river. Recognizing how unhygienic this practice was, he began looking for solutions. Later, he discovered two springs in the northeast corner of the riverside city (now in the Temple of the Five Lords). Despite being just a stone's throw away from each other, the water produced by these two springs tasted vastly different. Fortunately, the water from one of them, the Fusu Spring, had a delicate sweetness and was, more importantly, potable. Su went on to teach the locals how to dig wells and composed a poem about it: "The Pavilion of Drinking".

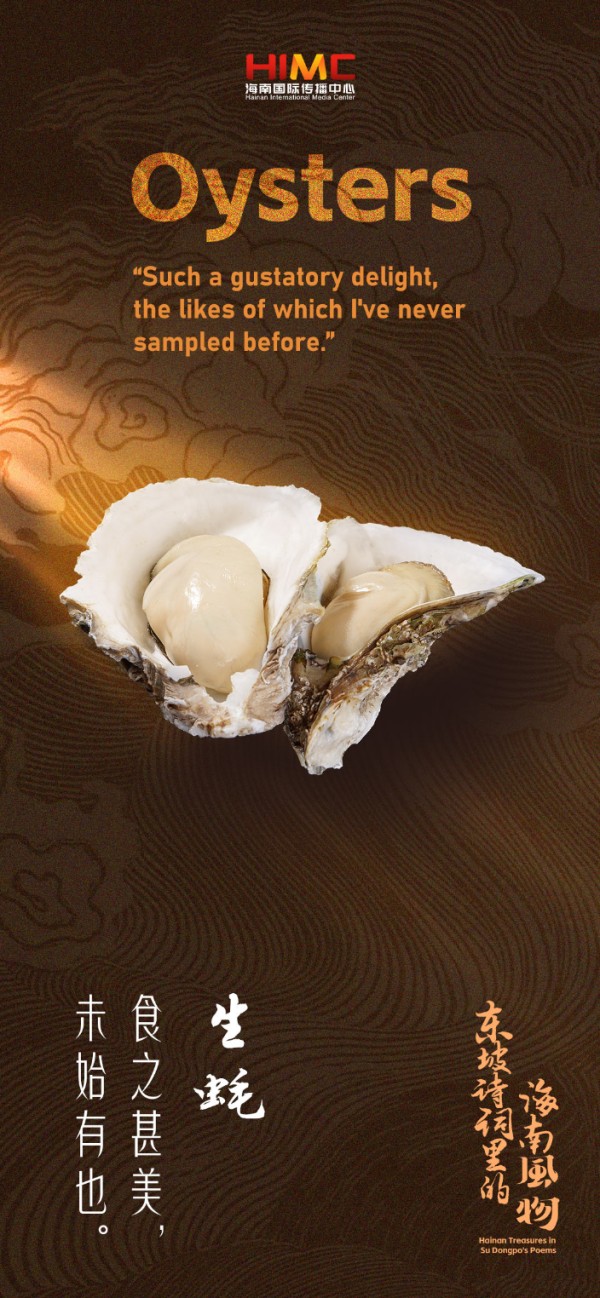

Backstory:

In addition to being a scholar, Su Dongpo was a foodie, and he was delighted by the delicacies of Hainan, his home in exile. In his article "Eating Oysters," Su Dongpo recalled the time when someone who lived by the sea sent him oysters. He described how he took out the oyster meat and juice and put them in a pot to cook in wine. He then took some of the larger oysters and roasted them over fire. He was enamored by their unique taste. Tongue in cheek, he also warned his son Su Guo not to tell anyone about Hainan's delicious oysters lest scholars still in their posts heard about them and ask to be banished to Hainan.

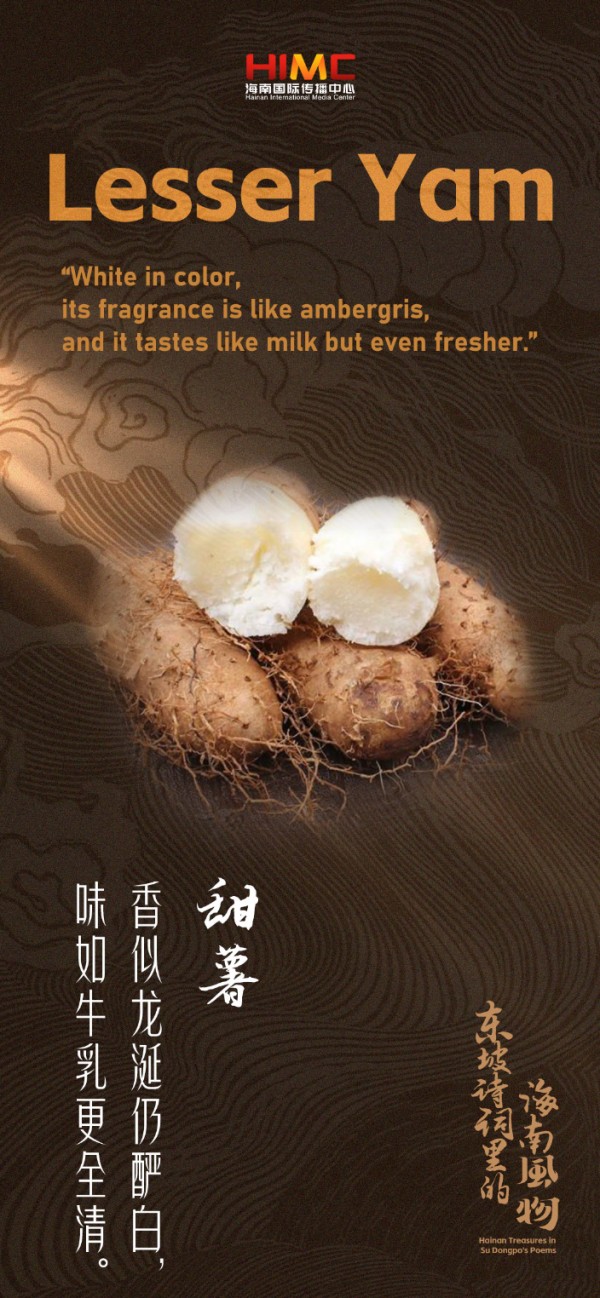

Backstory:

During his stay in Danzhou, Su Dongpo recorded in "Notes on Tubers" that although Hainanese grew wheat and rice at that time, no serious effort was put into it. Since there was not enough rice, people made porridge with local yams of various kinds. His son Su Guo even "developed" a new way to eat this "mountain delicacy" - "Jade Grist Soup." Unsurpassed in color, aroma, and flavor, Dongpo was very much taken with this concoction, describing it thus: "Not even the taste of the finest of dishes esteemed by emperors of old can surpass that of Jade Grist Soup."

Backstory:

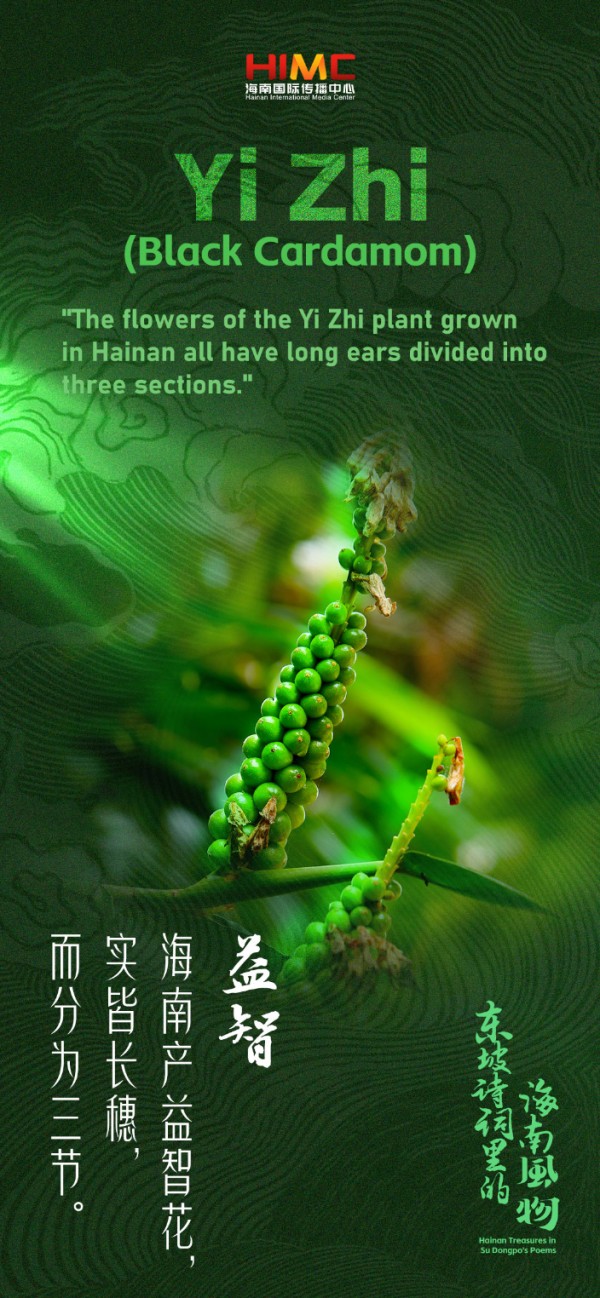

Despite his own troubles, Su Dongpo still cared about the suffering of the people, recording the effects of various medicinal compounds in his essays. In his essay, "Notes on the Yi Zhi Plant," Su described the growth characteristics of the Yi Zhi (Alpinia oxyphylla) plant and the medicinal efficacy of the fruits it produced, known as Yi Zhi Ren or black cardamom. As a medicine, he believed that while it could treat urinary issues, it had no effect on boosting intelligence, despite its name (益智 means "boost intelligence" in Chinese). At the end of the essay, he quipped, "Can intelligence really be found in medicine?"

Backstory:

When Su Dongpo first arrived in Hainan, he was not familiar with betel nuts, which are the fruit of the areca palm. He finally gave in and tried them after much encouragement from the locals. In his poem "Eating Betel Nut," Su described his fear when he first tried betel nut: "I was afraid I would pass out, so I spat out about half of it while I chewed." As he chewed, however, he suddenly felt a sweet aftertaste: "It's quite harsh and cool at first, but its charming flavor eventually reveals itself." He went on to describe the physical characteristics of the areca palm's branches, buds, and the betel nut itself, recording its purported "miraculous" effects: "As a medicine, it can cure stubborn malaria, relieve constipation, and treat diarrhea. How is it possible that one fruit can do so much?"

(Warning: betel nut is classed as a level 1 carcinogen by China’s State Administration for Market Regulation and a Group-1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization. Prolonged use of betel nut increases the risk of oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal cancers and may cause damage to teeth, gums, and oral mucosa.)